Article by Vera Zonneveld

Discrimination and exclusion appear at many levels in society, starting from the most basic human need – 1 in 10 people in the world lack access to safe and clean water. Although safe and clean drinking water is internationally recognized as a fundamental human right, marginalized groups, including women, children, refugees, people with disability and Indigenous people, are often discriminated against and excluded from safe water access.

Despite the international recognition of the right to water, examples from throughout the world illustrate stark inequalities between groups with different demographics, such as religion, socio-economic status or ethnicity.

For instance, asylum seekers and migrant workers are often not provided with sufficient water facilities by states. Caste-based discrimination in South Asia denies Dalits (or Scheduled castes) access to natural water resources. And in Europe, Roma communities lack access to running water and sanitation more often than the majority population. Moreover, water supplied to Roma communities more often contains contaminants and is not monitored to comply with safety standards. Other forms of identity that intersect with water inequality are elaborated on below.

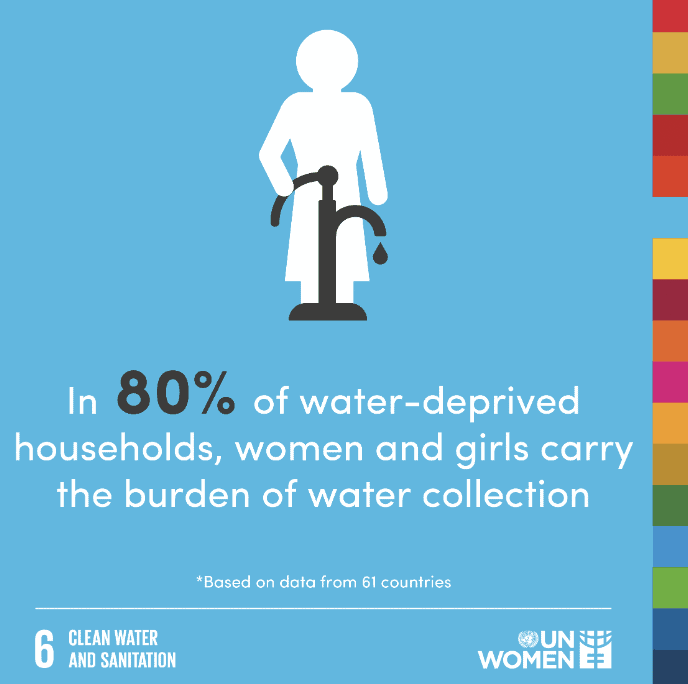

Gender and Sex

Women are disproportionately affected by climate change, especially when it comes to water-related needs. In parts of the world, women carry the burden of domestic water-related tasks due to assigned gender roles. Especially in sub-Saharan Africa, collecting water is mainly carried out by girls and women – they can spend up to 6 hours fetching water every day. This affects girl’s opportunities to enjoy education and eventually results in discrimination against women on the labour market. In addition, girls and women can face physical and sexual violence when they travel to collect water or to use public sanitation services. Despite their important role in domestic water management, women are often excluded from decision-making related to water issues. Also at a regional level, the role of women is not recognized as only 26% of countries actively take into account gender in designing water management practices.

Recognizing the gendered aspect of water management is important, as increasing pressure on natural water resources due to climate change increases women’s vulnerability and risk of facing violence. Recognition and support of women’s crucial role in water-related practices is also vital to support the survival and well-being of the families and communities who rely on these women.

Socio-economic status

Rapid urbanization in many places increases the number of people lacking access to water facilities. The development of public water services cannot keep up with the increasing demand and this especially affects poorer neighborhoods. The unequal distribution of water access is illustrated by comparing maps of municipal water access and districts by income in Lima; it shows that lower-income corresponds with lower levels of municipal water provision in the city. Especially in informal settlements, – places where people build (temporary) shelters without formal planning norms or land rights – infrastructure is generally lacking. This ultimately forces residents to spend a disproportionately large part of their income on bottled water. Governments often are not willing in investing in public services, fearing to send out a message of formalizing and legalizing these informal settlements. In addition, residents of informal settlements don’t claim water rights as they fear eviction when being in contact with authorities. These places should be recognized as places where different grounds of discrimination intersect, as poverty is often linked to other grounds of discrimination. Adopting an intersectional approach in water governance can help to protect the human rights of the most vulnerable populations with measures tailored to their needs.

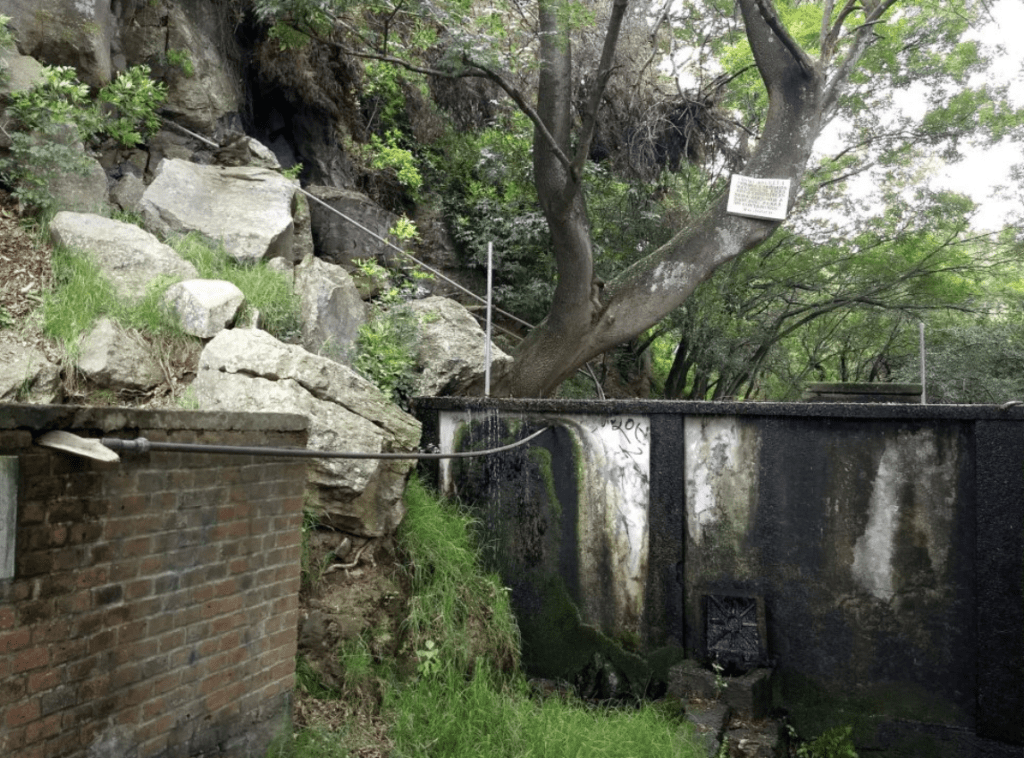

Indigenous water access

In the context of globalization, urbanization and privatization of water, Indigenous people have increasingly lost access to clean water sources. Despite a century-long connection to their land, Indigenous people have often been denied rights over water resources. The San Lorenzo Huitzizilapan Otomí indigenous community, in Mexico, has a community-based approach to water management of their forest and water resources. The community autonomously manages their water supply, by piping water from the Chichipas spring, since 1960. However, the National water law of 1990 doesn’t recognize their right to water and has allowed the distribution of water permits for anyone who applies for a permit. Since then, restrictions by the national water commission Conagua have been put in place and have allowed companies to extract water from resources on Indigenous territories. Similar problems of overexploitation, pollution and droughts threaten water access and the health of Indigenous people globally. Therefore, legal recognition of Indigenous rights to water is essential to protect Indigenous water access. In addition, empowering Indigenous people and their practices supports them in their protective role over the ecosystem – an ecosystem we all rely on for our survival.

With these examples, UR wants to highlight that ensuring safe water access for all goes beyond technical solutions. Instead, it requires redirecting attention to the most vulnerable groups – to achieve equal enjoyment of our human rights, our focus should be on improving the situation of those vulnerable groups who are most affected and enjoy the least power. Therefore, this also calls for recognizing the role that historical patterns of racism, coloniality and power play in the current provision of basic human needs by public authorities.

What role does intersectionality play?

Different identities and communities are not able to enjoy their human right to water fully as a result of direct and indirect discrimination. Denied access to water causes a large group of people globally to miss opportunities to follow education or enjoy a healthy life. In addition, UR recognizes that minority populations, such as Indigenous communities, and vulnerable groups including women play a crucial role in preserving the functioning of ecosystems and our societies. Society at large can benefit from redirecting energy to policies that empower vulnerable people and protect universal human rights. Thus, tailored policies should be developed to achieve equal access to water and sanitation services. Naturally, equal water access can not simply be achieved by treating everyone in the same way. Instead, special temporary measures that focus on closing the equality gap that focuses on improving the situation of marginalized and disadvantaged communities should be implemented.

To accomplish this, UN-Water proposes some concrete measures that include the identification of discriminatory practices, strong anti-discriminatory legislation, and monitoring and participation of marginalized people in decision-making. Disaggregating data by sex, age and other demographics is important to reveal existing inequalities. However, data collection to identify discrimination is challenging because official data is often not collected when it concerns those who are neglected. Still, increasing data collection is essential to identify the root causes of discrimination. A strong legal framework should recognize the human right to water without discrimination and can be used to officially establish Indigenous ownership over natural resources.

UR agrees that when policies are implemented, strong monitoring systems should be in place to track effectiveness. In addition, monitoring increases the accountability of states to achieve the targets they set. A human rights approach to water access also includes participation. Participation of those who are affected by policies around water access contributes to better implementation and more effective measures that adapt to local knowledge and needs. Transparency, access to information and inclusion of all stakeholders is essential for the development of successful solutions. To make sure marginalized groups can be included in decision-making, barriers to participation should be identified and removed. Consultations should be accessible to those who are physically disabled or to women with care responsibilities. Moreover, cultural barriers such as fear of speaking in public, taboos and potential discrimination, require awareness and attention. It takes willingness, time and effort to accommodate and include the voices of those who usually remain unheard.

Sources

De Albuquerque (2014). UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to

safe drinking water and sanitation. ISBN: 978-989-20-4980-9

Emilio Godoy (2021). Indigenous Peoples in Mexico Defend Their Right to Water. (2021, September 18). https://www.globalissues.org/news/2021/09/18/28780

European Roma Rights Centre (2017). “Thirsting For Justice – Europe’s Roma Denied Access To Clean Water And Sanitation”. Budapest: European Roma Rights Centre

Gerlak, A.K.; Louder, E. and Ingram, H. 2022. Viewpoint: An intersectional approach to water equity in the US. Water Alternatives 15(1): 1-12. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol15/v15issue1/650-a15-1-1/file

Harris, B. (2020, November 18). Water Inequality in Lima, Peru. Urban Water Atlas. https://www.urbanwateratlas.com/2019/05/11/water-inequality-in-lima-peru/

Healthwire Bureau. (2019, June 24). One in 10 people globally don’t have access to safe drinking water: UN report | HealthWire. HealthWire | Wellness at a Click. https://www.healthwire.co/one-in-10-people-globally-dont-have-access-to-safe-drinking-water-un-report/

Hidalgo, L. (2023). The danger of gender-based violence in water collection activities. IUCN. https://genderandenvironment.org/the-danger-of-gender-based-violence-in-water-collection-activities/

Reid, K. (2023). Global water crisis: Facts, FAQs, and how to help. World Vision.

Thompson, J. L., Gaskin, S., & Agbor, M. A. (2017). Embodied intersections: Gender, water and sanitation in Cameroon. Agenda (Durban), 31(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2017.1341158

Un-Water (2022, September 8). Eliminating Discrimination and Inequalities in Access to Water and Sanitation | UN-Water. UN-Water. https://www.unwater.org/publications/eliminating-discrimination-and-inequalities-access-water-and-sanitation

Un-Water. (2022). Water and Gender | UN-Water. UN-Water. https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-and-gender

United Nations (2015). International Decade for Action “Water for Life” 2005-2015. https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/gender.shtml

UN Women. (2019). SDG 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs/sdg-6-clean-water-sanitation