Authors: Nico de Leeuw, Rosa Jorba

“Every two weeks, a language vanishes, taking invaluable cultural heritage with it.”

According to UNESCO, 40% of the estimated 7,000 languages spoken worldwide are in danger of disappearing at this moment. Every two weeks, another language dies with its last speaker. According to different expert’s projections, 50 to 90 percent of all languages are predicted to disappear by the next century. Languages foster feelings of identity and belonging. They hold customs, values, culture, practices, knowledge of the environment, communal law, history and ancestry within them. When a language dies, all of these elements die with it.

Globally, there has been a common effort to preserve the diversity of indigenous languages. The United Nations General Assembly declared the period from 2022 to 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (IDIL) in order to encourage the preservation and promotion of Indigenous languages around the globe.

Indigenous communities have transmitted their language over generations through oral communication alone. This lack of written records makes them more vulnerable to disappearing. When a language is lost, the teachings and culture disappear with it. Indigenous teachings are often dismissed, instead of being considered equal to other languages. Indeed, Indigenous teachings are already kept out of important spaces, such as educational institutions.

When Indigenous languages disappear, more than just a language is lost. Indigenous languages contain a lot more than just words: they hold wisdom, stories, and intergenerational knowledge.

Language Loss is Colonial

Historically, Indigenous communities have relied on the oral transmission of their languages in order to preserve knowledge, customs, and traditions across generations. However, colonization and forced cultural assimilation have put these languages in danger, with many now facing extinction. Languages do not simply disappear out of nowhere. Language loss is a symptom of colonial violence, of a system actively working towards social and cultural hegemonization and assimilation of the people living in colonized land.

Some of the key factors that contribute to the increase in language loss are the lack of institutional support, forced displacement due to land dispossession, aging population of native speakers, globalization, and linguistic discrimination (also known as glottophobia). With the exemption of the population of native speakers aging as a factor contributing to language loss, all factors lead back to colonial structures.

The lack of institutional support that many Indigenous language speakers have to deal with also links to linguistic discrimination (glottophobia). In cases of glottophobia, individuals are treated differently based on their language, accent, or vocabulary. Indigenous languages are dismissed as ‘inferior’ or even referred to as dialects instead of recognized as real languages. This linguistic discrimination leads to limited employment and fewer educational opportunities for speakers of these languages, which then further contributes to cultural assimilation and a loss of identity.

“When a language fades, identity is lost.”

Language and Land

Indigenous languages and the land are intertwined on mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical levels. In some ways, they are one and the same. The relationship between language, culture, and the land inherently comes with responsibility to the land. Because Indigenous language and the land are inseparable, teaching and transmission of the language needs to take place on the land itself, which is now often threatened by colonial efforts.

“Language is land, land is language.”

Because language and land are so intertwined, they teach unique ways of relating to the world. Understanding and speaking an Indigenous language means understanding the relationship to the land and the environment. With the loss of Indigenous languages, we also lose a way of understanding the environment.

Indigenous Language Loss in Colombia

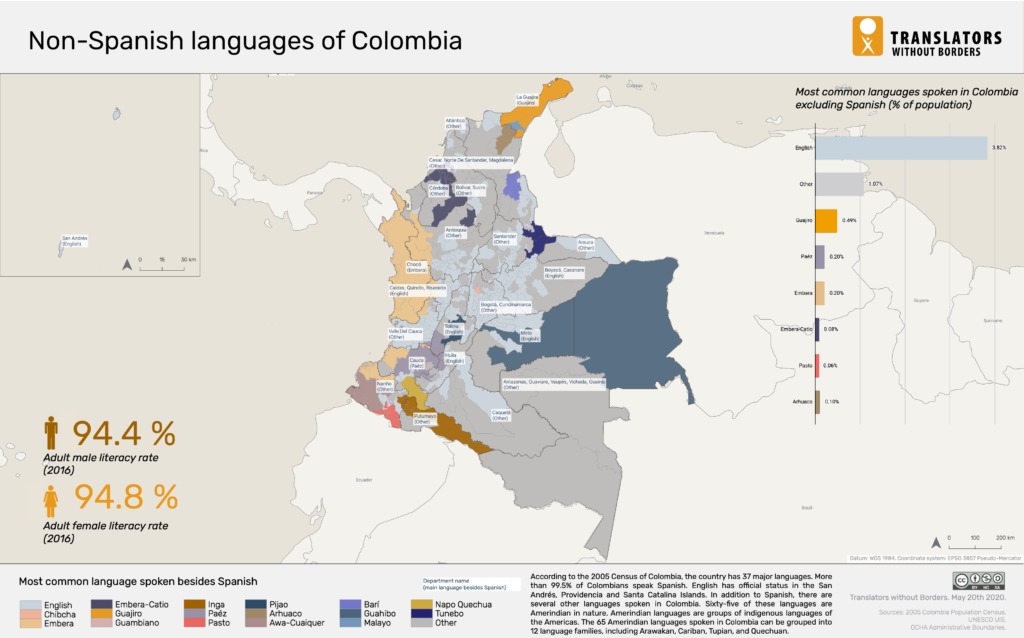

Focusing on a concrete country, Colombia is one of Latin America’s most culturally and linguistically diverse nations. According to the Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia (OINC), out of the 69 languages spoken in Colombia, 65 are Indigenous. Therefore, protecting and revitalizing these languages is a national priority. These 65 languages spoken in Colombia can be grouped into 12 language families, including Arawakan, Cariban, Tupian, Chibcha, and Quechuan.

Quechua, also known as Inga, arrived in Colombia with the Inca expansion. Various hypotheses suggest that its use spread during Spanish colonization, as Spanish conquerors used it as a pidgin language – a communication system that develops to interact when a common language does not exist – to communicate with diverse Indigenous communities. In Nariño, Quechua’s influence is evident in the street names, reflecting deep cultural integration. However, it is not clear if this presence has pre-Columbian roots or is a development of early colonial times.

In 1962, Indigenous peoples started to reclaim their linguistic rights which had been taken away after the arrival of Europeans to America. However, the decisive point was in 1991 with the new National Constitution, when Colombia was acknowledged as a multicultural and multilingual nation with the recognition of Indigenous communities as legitimate. It was a very important acknowledgement for them to give value to their languages as central to their identity. Although Spanish was still designated as the official language of the country, the state would also guarantee bilingual education and respect for their cultural identity (Constitución de Colombia, 1991).

The current situation in Colombia is still challenging. Indigenous groups find it necessary to learn Spanish for the most basic services as it is needed for education, healthcare, and political participation. Therefore, the dominance of Spanish is significantly impacting Indigenous communities, making Indigenous people feel invisible within their own country. According to the affected groups, Indigenous languages are under serious threat and a linguistic hierarchy remains prevalent.

“Language is the connective tissue of Indigenous cultures”

Spiritual leader “Mamo” of the Kogi Indigenous community at Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Kogi belongs to the Chibchan language family.

As the following map shows, in Colombia, there is still a tendency to focus on English-Spanish bilingualism at the expense of Indigenous languages. Despite the richness of these languages, Spanish remains the dominant one, spoken by over 99.5% of the population. Even though the Colombian Constitution recognizes the existence of Indigenous languages, government bilingualism programs have prioritized English over them, putting linguistic diversity at risk. This has been caused by the dramatic reduction of the use of Indigenous languages and their accelerated replacement by the languages of the majority of societies.

It is important that a record of threatened languages is kept, as in some cases, languages can be revitalized (“resurrected”) even decades later after being lost. To keep a small record of the language Quecha, we have decided to add a Quechan poem to this article. In our interpretation, it touches on the personal experience of language loss.

Poem written in Quechan, by Olivia Reginaldo.

Simi

Kay simiy ruwasqaykita atipanchu

qilla qalluy

qulluypaq qillqan

Kay simiy kasqaykita kamarikunchu

chukchu kichka

chikan kanchu

Kay simiy ripusqaykita aypanchu

nanayniy ninay

niy nina

Simi

My words cannot conjure the things you do

my idle tongue

writes toward a vanishing

My words cannot enclose all that you are

a trembling of thorns

absolutes exist nowhere

My words are no match for your retreat

give voice to my affliction

say fire

Language Revitalization

Efforts to preserve and revitalize Indigenous languages are a race against the clock, as most fluent speakers are elderly. “Language learning should be restorative and healing, but it’s always in the back of your mind…you’re trying to gain so much knowledge from this person before they pass. It’s really hard to learn when you’re feeling stressed out,” Sandra Warriors, who is learning the two endangered languages of her parents’ family line, says in an interview with CBC.

The low availability of learning resources of Indigenous languages also adds to the difficulty of language revitalization, as well as the challenge in finding immersive environments. In these types of environments, languages are picked up more easily because the speaker constantly hears and speaks the language. For most Indigenous-threatened languages however, there are so few speakers left that immersive environments simply do not exist.

Language Revitalization as Decolonization

Despite the challenges, Indigenous language revitalization is often very rewarding for communities. Language revitalization can serve as a bridge between generations, where elders actively pass down their language and knowledge to keep cultural heritage alive. Language revitalization is not only about expanding the number of speakers, it is also about language conservation and – in today’s digital age – about accessibility. Initiatives such as First Voices (a collaborative platform to share Indigenous languages and knowledge) use modern technology to preserve and share threatened languages.

Having established language loss as a consequence of colonization and cultural assimilation, the act of revitalizing these languages can be considered a process of decolonization. As long as (neo)colonial structures are in place, Indigenous languages will remain threatened. The fight against Indigenous language loss is therefore a fight against colonization.

“Wanee anüiki nnojotsü joulain”

“One language is never enough”

(in Wayuu, an Arawakan language spoken in northeastern Colombia)