Authors: Francisca Seabra and Rosa Jorba

The rise of soybean farming in Santarém, northeastern Brazil, has brought multiple social, environmental, and cultural consequences. From deforestation and mercury contamination to the displacement of Indigenous communities due to large-scale infrastructure projects, the case of Santarém illustrates the threats faced by many territories across the Amazon and beyond as a result of agroindustry expansion.

United Rising had the pleasure of interviewing Indigenous activist Viviane Borari. Through her lens, we gained sharp insight into Amazon’s challenges and the direct responsibility of the major corporations behind them.

Who is Viviane Borari?

Viviane Borari hails from Alter do Chão, an indigenous territory in the state of Pará, Brazil, where she has deep roots in the Borari community. Viviane initially studied civil engineering but switched to environmental engineering once she realized it did not align with her beliefs. She is now finishing her education in audiovisual technologies, equipping her with tools to bridge traditional knowledge and modern advocacy. Her father is a professor, her aunt a lawyer, and her friends are forest engineers, all together, they have been adapting to the changing circumstances to help as much as they can. Viviane’s early years were steeped in the rhythms of the Tapajós River and its surrounding forests. Growing up in Alter do Chão, her life revolved around fishing, swimming, and communal gatherings by the river. “The river was our lifeline” she recalls, “it gave us food, joy, and a spiritual connection to our ancestors.” She fondly remembers traditions like “puxirum,” where families would gather to share food, tell stories, and strengthen their bonds. However, the idyllic landscape of her childhood has changed. “The forests are burning, the river is poisoned, and the land is being taken from us” she laments. The once-abundant ecosystem is now under siege, threatening the way of life that had sustained past generations.

Brazil’s pressing reality

The Brazilian Amazon rainforest, often referred to as the “lungs of the Earth”, absorbs vast amounts of CO₂ and serves as a biodiversity hotspot with an incredible array of plant and animal species. However, this vital ecosystem is under severe threat from deforestation, habitat destruction, pollution, and the expansion of large-scale infrastructure projects, many of which are driven by Brazil’s booming agricultural sector. These all have something in common: the plan of big corporations to expand their activities in the Amazon.

A walk through the expansion of the agroindustry in Santarém

In the late 1990s, the expansion of the agroindustry became prominent in Santarém through the introduction of mechanized soybean farming. The region’s apparent suitability for large-scale agriculture, characterised by rich soils and logistical advantages such as the B-163 highway, the Teles Pires-Tapajós waterway and the Cargill port, placed Santarém as the strategic centre in global agriculture trade.

Cargill, a US multinational food corporation, is one of the largest global traders of soy operating in Brazil and one of the biggest contributors to deforestation. Alongside major industries and associations of Brazilian oil and cereal producers, the company has been expanding its soil plantations into the Amazon rainforest. Cargill has faced accusations of complicity in the displacement of Indigenous communities, as its operations and those of its suppliers often invade traditional lands. Viviane recalls how, nearby Vera Paz, a cherished community beach and cultural gathering space, was destroyed during its construction. “It’s not just the land they took, it’s our history, our identity”. Following accusations from Greenpeace, the major food corporations signed a soy moratorium in which they claimed to only purchase soy from producers who did not engage in new deforestation from that point forward. However, despite public commitments to eliminate deforestation from its supply chains by 2025, investigations have revealed that Cargill continues to source soy from these areas and that this measure did not help curb deforestation.

The environmental impact of these activities extends above deforestation. Industrial and agricultural operations in the Amazon have led to severe river contamination, posing significant health risks to local populations. In the Low Tapajós River region, mercury contamination has reached alarming levels. In fact, Viviane explained how she tested positive for mercury, and so have many others in her community – over 75% of residents tested have mercury levels in their blood exceeding the safety limits established by the World Health Organization.

She also condemns the government’s support for harmful agribusiness practices, including the use of banned pesticides and unchecked deforestation, “our leaders are selling the Amazon piece by piece”. Investments in infrastructure by both public and private entities established a phase of growth, with organizations like EMBRAPA (the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation) conducting soil quality studies and the Banco da Amazônia offering financial support to incoming farmers.

Future plans of Santarém

The future of the region looks bad, as the government continues to support new infrastructures to expand the industry without considering the Indigenous people and the balance of the forest.

The Brazilian agribusiness, Cargill among them, are now pressuring the Government to construct the Ferrogrão railway, a large-scale infrastructure project, partly funded by Chinese investments, aimed at supporting Brazil’s agricultural expansion. This railway is intended to transport soy and other commodities from Mato Grosso, the country’s agricultural hub, to the port of Santarém. While some enterprises argue that the project will improve economic efficiency, it also raises significant environmental and social concerns. The proposed route passes through environmentally sensitive areas, including six Indigenous territories, like the Munduruku and Kayapo. “We are not against development, we are against development that brings death and destruction”, Viviane warns.

Another project that brings worries to the community is the Hydroelectric Complex of the Tapajós. The project consists of a complex of hydroelectric dams on the Tapajós and Jamaxin rivers aimed at transforming the river into a navigable waterway and. Similar to the Ferrogrão railway, the project intends to facilitate the transportation of soybeans from Mato Grosso to other ports. This proposed dam, if it goes ahead, will permanently flood about 72 thousand hectares and result in a loss of at least R$ 11.8 billion in social value. Both the federal agency overseeing indigenous affairs (FUNAI) and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) opposed the project for the expected impacts on indigenous communities. Currently, the project is suspended and under a state of uncertainty. Viviane’s feelings of sadness, sometimes rage, and frustration are understandable when the state of affairs surrounding her looks like this.

Indigenous initiatives

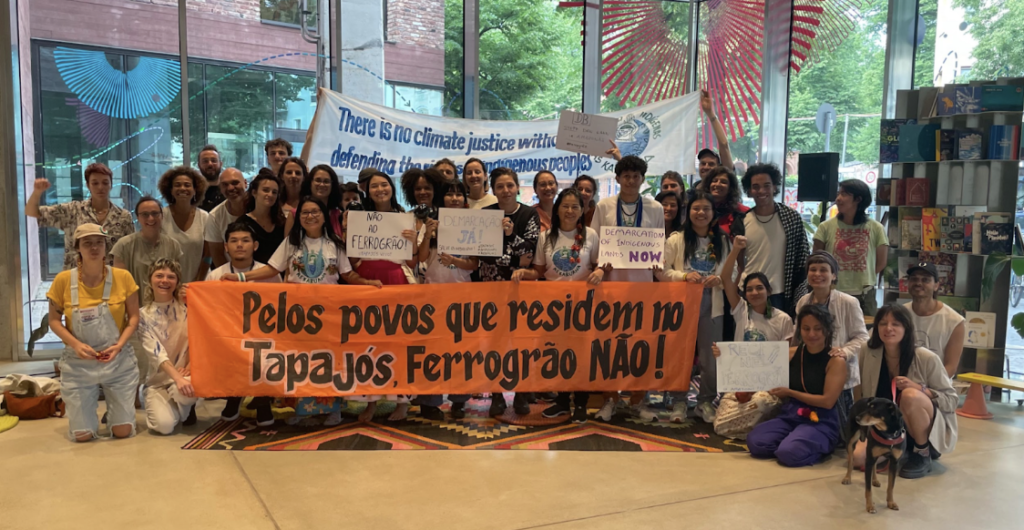

Communities in the area are at the forefront of stopping illegal activities in Brazil and are not ready to let any of this slide. Viviane Borari impersonates precisely this force and dedication to the protection of the Indigenous communities, balancing multiple roles as an activist, filmmaker, and cultural preserver.

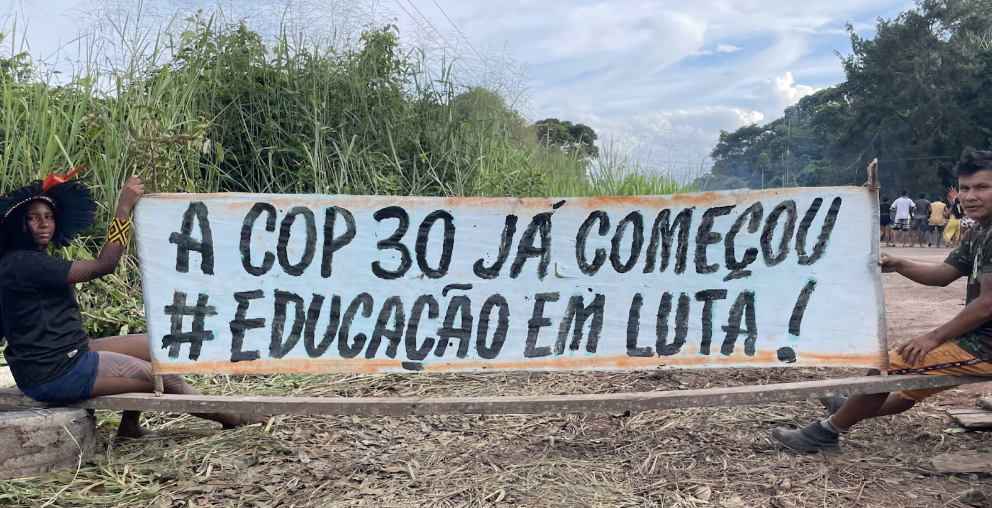

As a vital figure at Tapajós Vivo, a grassroots movement advocating for socio-environmental justice, she defends the way of life in the Tapajós Basin. What started as a movement of resistance against the Hydroelectric Complex of the Tapajós has now turned into a key movement that mobilizes communities, through projects, campaigns and importantly, training, “Education allows us to build partnerships and strengthen our fight”, Viviane points out.

Viviane also explains her work with Treesistance, an initiative aiming to bridge ancestral and contemporary realities through storytelling. Treesistance portrays the stories of the Pajes (Shamans) of the lower Tapajos, talking about stories of Indigenous resistance and about the spirits of the forest.

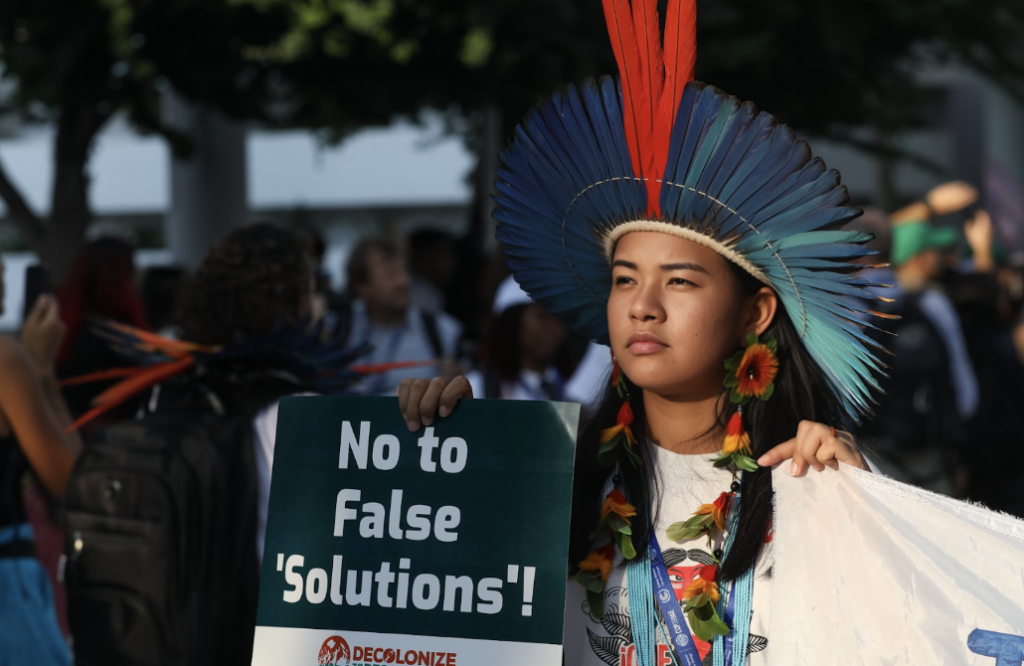

Global responsibility

For Viviane, tackling Amazon’s challenges requires systemic change and a global commitment to sustainability. She calls for stronger environmental protections, government accountability, and greater representation of Indigenous voices in decision-making spaces, “we need leaders who understand the reality on the ground”. She also warns against market-driven solutions like carbon offset programs, which she views as exploitative. “We don’t need deals that allow corporations to pollute elsewhere while pretending to protect the Amazon”, she says, instead advocating for direct investment in local communities and sustainable practices.

A beacon of hope

“I believe we need to cultivate more respect, for Mother Earth but also for people in general, and provide support to those that particularly need it. We, here in the Amazon, in reality are surviving, we want to live, but we are just surviving. So we need people to become more aware, and research more, because there is so much content, so much information about everything in the world, and I think researching a little bit will also bring more awareness about what is happening, about what people are suffering, and that, today, the planet is still resisting because of the people who are protecting the forest.

So, we need to strengthen this even more, and people should be protectors of the forest, not only Indigenous people but non-Indigenous people as well. I think that’s what is necessary given everything we are living through. And don’t let immediacy slow down thoughts of solidarity and respect, because that’s exactly what the system wants, the system wants to make you chase after things that are unattainable, and you don’t realize that there is so much good here that just needs to be cared for, because then we will live better.”