Authors: Marta Fontana, Soňa Sopirová, Zsófia Rába

1. Introduction

“We think of our body as our first territory, and we recognise the territory in our bodies: when the places we inhabit are violated, our bodies are affected, when our bodies are affected, the places we inhabit are violated.”

(Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 2017)

This powerful assertion, rooted in Indigenous feminist views, captures the profound relationship between gender, land, and resistance — describing a lived reality of countless Indigenous women whose bodies and lands are simultaneously subjected to violence. Gender based violence remains one of the most pervasive and devastating forms of oppression experienced by women, particularly Indigenous women who face overlapping threats from patriarchy, colonialism, extractivism and environmental degradation. These experiences reveal that the violence against women’s bodies mirrors violence against the physical lands they inhabit — a view underlying the core argument of this article.

With this article, UR aims to illuminate a truth too often overlooked: the climate crisis does not affect everyone equally. By applying an intersectional approach, we reveal how environmental breakdown magnifies long-standing injustices — including the rise of gender-based violence (GBV). This article examines how gender-based violence is a system of oppression rooted in patriarchal, colonial, political, social and economic inequalities – disproportionately affecting Indigenous women and shaping their struggles for survival, autonomy, and justice. It explores what GBV is, why Indigenous women are particularly vulnerable to it, and how environmental injustice and climate change intensify these forms of violence.

The experiences of women facing these intersecting crises inspire a radical form of defiance: embodied resistance. Rather than being solely sites of trauma, women’s bodies become instruments of political agency and transformation. Through their physical presence, collective action, and cultural practices, women transform what makes them vulnerable into a powerful source of resistance that disrupts systems of oppression.

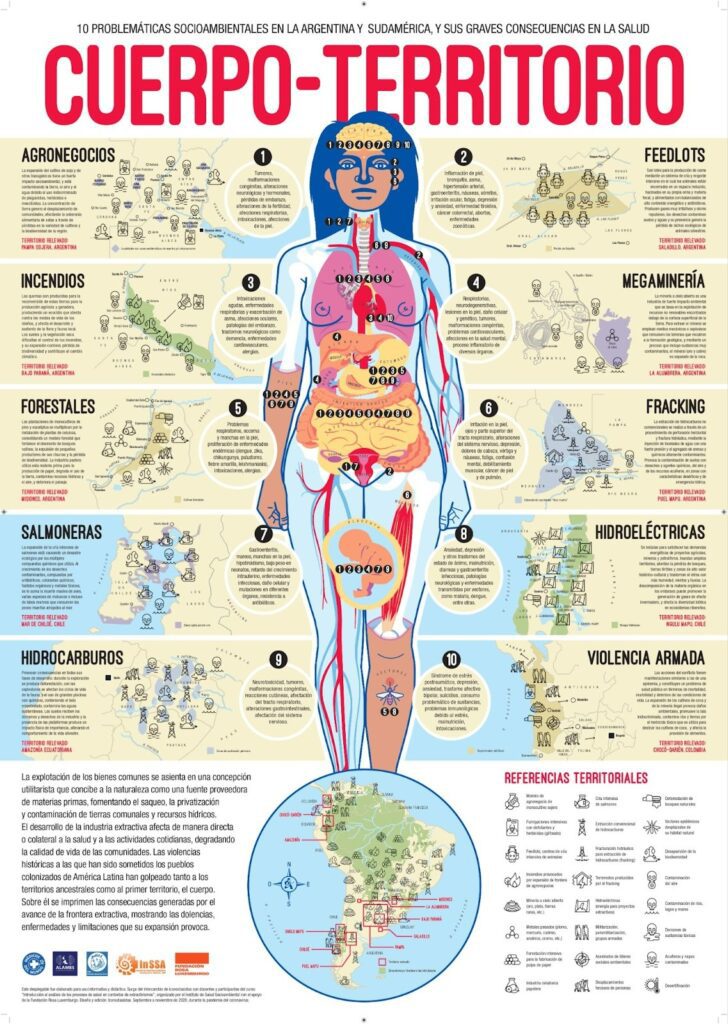

To illustrate this, the article showcases two concrete examples: the Ogoni women of Nigeria resisting the violence of oil extraction, and the Maya-Xinka women of Guatemala who conceptualise the cuerpo-territorio (body-territory) as both the first site of harm and struggle. These case studies reveal how women mobilise their bodies—through protest, ritual, healing, and everyday acts of care—to combat militarisation, extractivism, and structural gendered violence.

2. What is Gender-based violence and Embodied Resistance?

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to a wide range of different forms of violence that are employed against a person specifically because of their gender. These forms of violence particularly affect a vast majority of women and girls around the world. There are several forms of gender-based violence: sexual, physical, emotional or psychological, domestic, financial, and other harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage. GBV is deeply ingrained in the functioning of our societies, reinforced by structural, political, economic, and social imbalanced dynamics between women and men at multiple social levels. The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes violence against women as a global public health pandemic, with at least one in three women, over one billion, experiencing intimate partner violence, physical aggression, sexual violence or coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviours over their lifetimes.

The Intersection of Gender and Environmental Struggles

In recent years, the link between GBV and climate change has become undeniably evident. Research from the UN Spotlight Initiative has shown that GBV and climate change are deeply interconnected, as the climate crisis intensifies many of the social and economic conditions that fuel violence against women and girls. Climate-related disasters, rising temperatures and resource scarcity lead to displacement, increased poverty and inequality, food insecurity, and overall social breakdown. All of which heightens women’s vulnerability towards physical, sexual, psychological and economic violence. In other words, the socio-economic instability caused by the environmental crisis results in the intensification of harmful gender and power imbalances, resulting in increased rates of gender-based violence.

Not only does climate change intensify the effects of GBV, but it also undermines women’s ability to lead climate action. In fact, the participation of women in global efforts to mitigate climate change effects has proved to be essential. Across the world, women, especially Indigenous women, play a vital role in producing food, preserving biodiversity, and managing natural resources through sustainable practices rooted in their ancestral knowledge. Indigenous women are environmental stewards, community leaders and powerful agents of change. Yet, they face intersecting systems of oppression that limit their impact and capacity for decision-making and resistance. According to the UN, when women are empowered and included in climate strategies, communities become more resilient, sustainable practices improve, and climate goals become achievable.

Above all, Indigenous women are more vulnerable to GBV as they face overlapping forms of discrimination based on gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic marginalisation shaped by the enduring effects of capitalist, colonial and patriarchal oppression. Likewise, when Indigenous women are also environmental and human rights defenders, they are at particular risk of harassment, sexual violence and femicide, especially in the context of extractivist and environmental conflicts. For instance, when extractive projects pollute local water sources, Indigenous women must walk farther through likely isolated areas to collect water, making them easier targets for harassment or assault. GBV in the context of environmental crises functions as a double-edged dynamic: while the commodification of nature deepens the hardships women face, violence against women’s bodies becomes a deliberate strategy through which perpetrators further commodify and control nature. Indigenous women around the world have confronted GBV and environmental destruction, using their bodies and non-violent actions to reclaim autonomy over their ancestral land and bodies.

Female Bodies as Instruments of Resistance

Critical feminist theories have long stressed the potential of female bodies as sites of both struggles and resistance. The concept of embodied resistance refers to the use of the body as simultaneously the site, subject and instrument to overcome the struggle faced by the body. In other words, female bodies are not only where violence and oppression are experienced, but they can also become active instruments of confronting and challenging that violence. The gender theorist Judith Butler argues that resistance in itself is an embodied act that becomes most powerful when performed by those bodies deemed most vulnerable, violated and weak. Therefore, the public exposure and use of the body becomes a medium of political expression and resistance. In the context of GBV overlapping with environmental conflicts, women’s bodies are the point of intersection where power, violence and exploitation meet. When women reclaim their bodily space through protests, occupations, rituals, and public nudity, they are concretely using their physical presence to perform embodied resistance. Hence, they are using their own bodies as instruments of political agency that confront and disrupt systems of oppression, transforming what makes them vulnerable into a powerful tool of resistance.

3. Bodies of Resistance: How Indigenous Women in Nigeria Confront the Violence of Oil

In the Niger Delta, where oil stains the river and the air thickens with fumes, the Ogoni women’s body has become a contested territory enduring intersecting forms of violence as a result of colonial legacies, traditional male chieftaincy, extractivism and the relentless quest for power and money. Here, the female body becomes both a site and a symbol of oppression. Women in Ogoni communities, who traditionally collect and sell aquatic animals like crustaceans, clams, lobsters and shellfish along the coast, have been greatly affected by oil spills that pollute water sources and soil, transforming the region into an environmental disaster zone and imposing a burden on their lives. Because of this deep bond with their land, Ogoni communities historically prioritise protecting the environment, regarded not only as the source of their livelihood but also as the home of their ancestors.

“We were nothing to people. We were not regarded. That you would get to the place where people are telling them you are from Ogoni, they’ll say, ‘After all, you are nothing.’ . . . [They say] that you are not able to.”

Since oil was first discovered in Oloibiri in 1958, the region has suffered from various forms of injustice due to militarisation and relentless exploitation of the land and people by the government and multinational oil companies, where “violence becomes a crisis of everyday life.” This land, poisoned by decades of destruction and repression, represents a source of survival for the communities, particularly women, who uphold Ogoni tradition as primary farmers and traders. For Indigenous Ogoni women, rivers coated in black oil, fields choked by spills, and the acrid scent of oil hanging in the air became a constant reminder of the violence endured by both their land and themselves.

“Traditionally, when an Ogoni woman gets married, her husband is required to give her a piece of land to farm. It is from this farm that she feeds her family and grows food for sale in order to buy other staples.”

The violence experienced by Ogoni women is multifaceted, ranging from physical, psychological and environmental, with environmental degradation as one of its main drivers. Their traditional role, aimed at sustaining their community, makes them dependent on the land for food, income, and cultural belonging. Hence, the degradation of the environment becomes a real threat to their role in the community, but also a direct hindrance to their physical safety; not only are they losing their livelihoods, but also their physical safety and autonomy. Pollution from oil extraction destroys farmland, contaminates water, and undermines livelihoods, exacerbating their vulnerability to GBV, including forced marriage, early childhood marriage, rape, physical and verbal abuse, and incest. Sexual violence against Ogoni women functions as a weapon of humiliation and silencing, reinforcing gendered ideals of “putting women in their place”, often referred to as “rape of women in the name of maintaining peace and order.”

With the Niger Delta region dominated by a military presence for decades, security forces have prioritised protecting oil infrastructure over communities. In this context, women’s bodies become a vessel, a means to send a brutal message and humiliate Ogoni men at the height of demonstrations. The repression and violence experienced by Ogoni women reflect the damage done to their land: just as oil extraction leaves the Niger Delta scarred, women’s bodies suffer, devastating not only their land but also ripping their community apart.

Despite this, women of Ogoniland chose to act. For them, resistance has become a way of life, and to this day, they carry on their activities such as farming, trading, caring, as well as acts of resistance, protecting their land and community.

“Women were harassed on the way to their farms, on the way to their markets, in their villages minding their homes, and at night when they were asleep.”

They have learned to use their bodies as a weapon of protest – expressing their frustration, anger, and defiance through dance, songs, collective demonstrations and strikes, testimonies, or culturally specific acts, such as stripping naked or fighting “using the gu su”, an epitome of nonviolent resistance. For instance, when employing the “gu sa”, Ogoni women signal the movement’s peaceful intent by visibly replacing weapons such as the fist or gun with palm fronds – underscoring their value for their humanity and peace.

For Ogoni women, coalition-building was essential to confront their struggles, with gatherings playing a central role in the Ogoni Women’s Coalition, known as FOWA. These meetings were not purely strategic nor educational, but had deep spiritual meaning. Through activities like teach-ins, prayers, fasting sessions and vigils, women built their collective strength and generated positive power that sustained them in the face of repression. At times, women would blockade compounds, holding men “hostage” by preventing them from leaving while expressing their grievances through dance and songs. Historically, for Ogoni women, dance has been a powerful tool of cultural expression and a way of acknowledging their political demands. They transform their fear and anger into a collective courage, turning their bodies into instruments “dancing oppression and injustice to death”.

As one of the most powerful expressions of embodied resistance, women in the Niger Delta turned to what is known as “the Curse of Nakedness.” When their demands went unheard, they confronted the oil companies with a weapon both intimate and terrifying: the threat of stripping off their clothes, an act deeply feared and culturally significant. Nakedness of, particularly married and elderly women, serves as a form of moral punishment, believed to bring shame, madness or misfortune upon men who witness it. Resorting to the so-called “naked option” demands remarkable bravery, as women transform their own vulnerability into a forceful instrument of protest, channelling the pain of a community whose land and livelihoods have been exploited.

“If, having taken this position today and the government goes ahead to resume oil exploration, we, the women of Ogoni, will come out en masse and protest naked until the world hears us.”

4. Cuerpo-Territorio (body-territory): How Indigenous Women in Guatemala Turn the Body into a Place of Resistance

In Guatemala, where the brutal legacies of civil war intersect with the relentless advance of extractivism, the Indigenous woman’s body has become a definitive political battleground. For Indigenous groups primarily found in Guatemala, violence does not come from a single source; it emerges from a devastating convergence, an entronque patriarcal (patriarchal junction), where ancestral and colonial forms of patriarchy fuse to establish a symbolic order of ownership over their very existence.

This profound, intersectional crisis, rooted in their age, gender, ethnicity, and geography, forces many to confront a chilling truth: their bodies are treated like their ancestral lands: as raw, exploitable “territories” subject to theft and degradation. As Maya-Xinka activist and leader Lorena Cabnal observed:

“to be an indigenous woman in this context is complex because your body is converted into the first territory of dispute for patriarchal power“.

From this lived experience, Lorena Cabnal, a Maya-Xinka communitarian feminist, coined the powerful concept of cuerpo-territorio in 2010. It challenges the colonial logic that separates body from land, asserting instead their ontological unity. In this framework, the Indigenous woman’s body becomes the “first territory of dispute”, a place where historical and contemporary oppressions collide, and where new forms of resistance emerge.

This idea stands at the heart of communitarian feminism, a movement originating from Indigenous women of Abya Yala (Indigenous term that indicates the American continent ), including Maya women in Guatemala and Aymara women in Bolivia. It argues that patriarchy is the foundation or “system of all oppressions”. This oppressive system uses colonialism to dominate the bodies of people, the land, and nature. By conceptualising the relationship between body and land as an ontological unity, the cuerpo-territorio framework exposes how external political and economic forces, namely neoliberal extractivism, replicate the violences of colonialism upon both the physical body and the communal earth.

For Indigenous women in Guatemala, violence is inseparable from the country’s history of conflict and dispossession. The Guatemalan postwar landscape (following the 1960–1996 internal armed conflict) has been tragically characterised by high rates of violence against women (VAW) and femicide. This context reflects enduring systemic barriers that are legacies of both colonialism and civil war, leading to Indigenous girls and women experiencing a “quadruple disadvantage“. Historically, the military leveraged wartime sexual violence against Indigenous women to dismantle social ties. Today, this systemic disadvantage, fueled by inequality, misogyny, and racism, makes violence feel “normal” or “natural” until consciousness is raised, as demonstrated by the experience of leader Elizabeth Vasquez.

This violence is acutely intensified by the extractivist economic model of the postwar era, particularly in regions like the Northern Transversal Strip (FTN). In these regions, capitalist expansion, especially palm oil cultivation, has introduced new forms of GBV. Maya Q’eqchi’ women resisting this model describe it plainly: “palm oil is a form of violence against women“. The industry’s arrival brings social fragmentation, economic dependency, and increased domestic abuse—further entrenching patriarchal and colonial hierarchies.

The power of cuerpo-territorio lies in showing that violence against Indigenous women’s bodies is not an isolated or “private” harm, but one layer within a larger constellation of patriarchal, colonial, and extractivist violences that intersect and reinforce one another. It transforms this recognition into a site of profound resistance, where defending the body becomes inseparable from defending the land and the community. Cabnal highlighted the “incoherence” of defending ancestral lands without simultaneously defending the bodies of women, asserting, “we cannot compartmentalise life”. This moment of awakening transformed the political struggle for the earth (territorio-tierra) into an inseparable struggle for women’s bodies (cuerpo).

The resistance employed by Maya-Xinka women is therefore deeply embodied, challenging the multi-sited nature of patriarchy. They insist that there can be “no decolonisation without depatriarchalization“. This practical, spiritual, and political struggle involves engaging with formal political structures to denounce abuses, resisting the extractivist model, and pursuing pathways of emotional and spiritual healing (sanación como camino cósmico-político).

For instance, Xinka women organised in the association AMISMAXAJ that defends the territorio-cuerpo-tierra not only through formal political advocacy but through everyday practices of care and restoration. Cultivating communal gardens (milpas) becomes both an act of sustenance and defiance, a way to heal the earth and their own bodies simultaneously. Through collective healing (sanación como camino cósmico-político), they recover traditional knowledge, rebuild community ties, and reaffirm their right to life, dignity, and autonomy.

The story of cuerpo-territorio reminds us that resistance begins in the body, extends to the land, and flows through collective memory. It teaches that liberation cannot be piecemeal, because to protect the Earth, one must also defend the women who carry her within them.

5. Conclusion

The stories of Ogoni women in Nigeria and Maya-Xinka women in Guatemala reveal a truth that cannot be ignored: GBV and environmental destruction are clearly mutually reinforcing crises. They are driven by the same forces, patriarchy, colonialism, and extractivism, that treat women’s bodies and the Earth as territories that can be violated, controlled, and exploited.

Yet, these forces reveal the opportunity for a transformative and intersectional resistance. When Ogoni women blockade oil sites with their bodies or Maya-Xinka women defend the cuerpo-territorio through healing, protest, and care, they transform the very space of vulnerability into a space of power. Female bodies become the first site of struggle, and simultaneously, a tool for liberation and change. Embodied resistance reveals that defending land is inseparable from defending those who hold ancestral knowledge, sustain entire communities, and protect the environment: Indigenous women.

Their resistance compels us to act. Supporting Indigenous and marginalised women is a necessary commitment for climate and social justice. We must amplify their voices, challenge the intersecting systems that endanger them, and join their call for a future where both land and bodies are treated equally with dignity, autonomy, and respect.

United Rising invites our community, partners, and readers to stand with these women by supporting grassroots defenders, sharing their stories, and pushing for climate policies that centre gender justice. Protecting the Earth begins with protecting those who defend Her.