Author: Marit Heppe

Lake Tarawera, the early morning of May 31, 1886, a short eleven days before the eruption of Mount Tarawera. A thick layer of mist hovers silently above the water, the mountain reduced to a ghostly outline. Yet, undeterred by the brume, Māori and European tourists alike had no trouble spotting the drift of a pale watercraft, double rows of people dressed in traditional attire, their hair plumed as for death—a phantom Māori waka (war canoe). Tohunga (priest) Tūhoto Ariki understood the phantom canoe as a bad omen. A prophecy and a warning that would be fulfilled on June 10, when Mount Tarawera burst open.

Like the phantom waka, the trillion plastic bottles thrown in and clogging the ocean serve as a bad omen, warning the world of disaster and death. The only difference: whereas the phantom canoe vanished as quickly as it appeared, plastic waste has long proved burdensome to its environment and continues to damage life within and beyond saltwater. With the ocean central to their identity, plastic pollution disproportionately impacts Māori, both in their cultural practices, well-being, and environment. As Aotearoa New Zealand is among the world’s most wasteful nations, a center of waste colonialism, and insufficient in its efforts to incorporate Indigenous knowledge or participation into local government decision-making, tensions between Māori and the New Zealand government have significantly grown.

A New Prophecy

As these pressures increase and threaten Māori ways of living, organizations and artists raise awareness about ocean pollution through traditional practices and stories. They speak through art to express, challenge, and inspire. Shaping perceptions and shining a light on ignored issues, art exposes the intersectional challenges they face. This stands at the center of United Rising’s mission: to explore storytelling as a key methodology for uncovering and advancing climate justice.

This article dives into the weight of storytelling through George Nuku, a Māori sculptor passionate about exploring the connections between oceans, plastic, and his native culture. Like Tohunga Tūhoto Ariki, in his art, Nuku also offers a prophecy and a warning: the ocean a hundred years from now if we do not change course. But he goes beyond this: stressing empathy, divinity, and connection rather than blame, fear, and contempt, Nuku’s story diverges from current climate conversations. By using the power of storytelling, his art not only constructs an image of the future ahead but also challenges our perceptions of plastic, relationships, and connection.

Who is George Nuku?

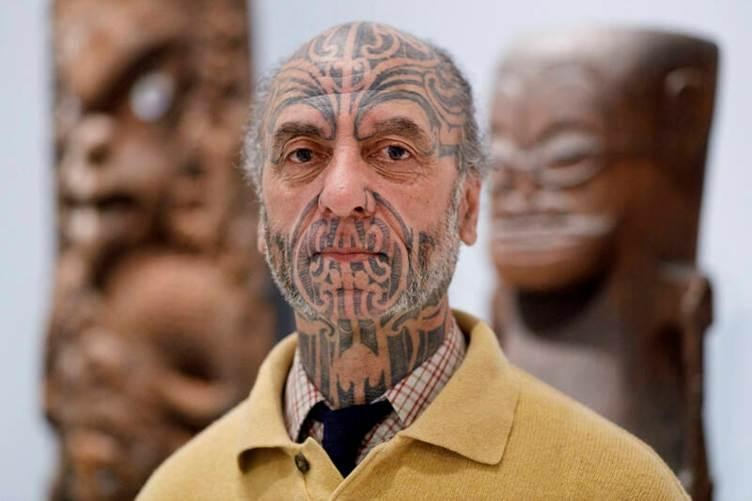

George Tamihana Nuku is a Māori carver and sculptor. He was born in 1964 in Hastings, Aotearoa New Zealand to the iwi (tribes) Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Tūwharetoa on his mother’s side, as well as of Scottish and German descent from his father’s side. He grew up in Omahu and moved to Napier, but currently lives between France and his home marae in New Zealand. He creates artworks with distinct connections to his traditional culture and history:

“I apply the knowledge of my Māori culture towards my art practice and basically every component of my life. And the idea is to surround my work to deal with the ocean because I come from an oceanic world, of the Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, the Pacific Ocean. And I’m part of a greater Polynesian family which stretches from Hawaii to the North in Rapa Nui Easter Island to the East and Aotearoa New Zealand to the South.”

Already interested in art from an early age, Nuku decided to study the subject at Massey University alongside sociology, geography, and Māori studies. After applying himself to art as his primary passion, he started his sculpting career with exhibitions in the Netherlands, Tahiti, Telluride, New York, and Paris. Initially working with bone, shell, and stone, Nuku channeled traditional forms of art into his artworks. However, after visiting the UK in 2006, his approach to his creations shifted, now incorporating ‘modern’ materials such as polystyrene and plexiglass into traditional sculpting projects. It is a practice that connects him to his ancestry. In an interview with ICT News, he goes as far as to say, “It was not me carving them, but the repetition of their carving that gave me a way of life.” Among his most popular works is the Bottled Ocean series, installations crafted entirely from recycled plastic while depicting powerful waka, mythological creatures, and magnificent sea life.

Beyond its significance to his own life, Nuku deems art extremely important in its potential to shift perceptions of wealth. According to him, artists are the ones who have the ability to keep the communication between humans and nature healthy.

“The role of the healers, artists, dreamers, and creative people has never been more important than it is now. We represent the antidote to the globalization of mediocrity in the name of money.”

As he states, by devoting our lives only to monetary values, we lose sight of the values that truly enrich and foster connections. With his art, Nuku intends to present a type of beauty and wealth beyond the monetary unit—a Māori way of understanding the world.

Māori and the Ocean

Native to Polynesia, Māori are the Indigenous people of mainland New Zealand. Māori oral histories describe their arrival after a series of canoe voyages in the early 14th century. Though all cultures maintain deep respect for the ocean, Māori beliefs place ocean life at the center of their identity, considering their connection with it a form of wealth. Moreover, according to Māori mythology, Waitā (ocean) is considered the territory of a multitude of ocean atuas (deities), Tangaroa being the greater god seizing control of all oceans and life within. Flowing from these atuas, the ocean relates to the fundamental Māori concept of whakapapa (genealogy). According to Nuku:

“The world I come from, this one third of the planet, is determined by one single thing: whakapapa. That has to say, everything has a lineage, everything has a mother and father, everything is related to everything else.”

Therefore, Māori consider the ocean taonga (treasured), both as their living ancestor and as a crucial element in their traditional practices and customs. The gathering of seafood, kai moana, and the right to harvest, mana moana, are both ways of sustaining communities and gauging the mauri (life force) of the ocean. Deterioration of the marine environment puts kai moana and associated traditions at risk, their disappearance threatening the passing down of Māori knowledge and practices.

In the past century, the state of Waitā has ebbed and deteriorated. In Aotearoa New Zealand, high levels of plastic pollution have been found in lakes, on the seafloor, and within common fish species, increasingly affecting the ocean’s mauri. But why is it that Māori face the brunt of plastic waste in Aotearoa? As plastic waste takes on a global role, anchored to international relations, it reflects the inequalities in its flows and management. A 2024 study on waste colonialism in Aotearoa shows that colonial systems have been the stepping stones to power imbalances in waste movements. Its legacy has paved the way to waste colonialism, “the practice of developed nations consuming excessively and exporting their waste to less developed countries”. With a substantive volume of waste from the Global North, large amounts are exported to vulnerable regions, exacerbating existing pressures on sovereignty, food security, and health. Therefore, it is also considered a strategy to “exert control over Indigenous lands and communities,” and undermine their right to self-determination.

For Māori, this came into being through historical colonization and dispossession of Māori land, ultimately leading to the relocation of iwi near sites of waste and pollution. Moreover, despite the 1840 Treaty with the British Crown, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which reaffirms the right of Māori to land and authority, institutional barriers substantially restrict the extent of Māori political authority. As a result, Māori face a disproportionate burden of waste, threatening their direct environments as well as ways of living, autonomy, and sovereignty.

Bottled Ocean: Plastic as Taonga

Considering plastic a representation of light and water, Nuku describes it as a testament to divinity. A fascinating material and something taonga, a statement that stands in contrast with the way plastic waste is disposed of. That is why he started his series of Bottled Ocean installations, each a depiction of the ocean’s condition a hundred years from the moment of creation. The series finds its roots in 2014, when Nuku was commissioned by the Taiwanese Museum of Contemporary Art to contribute to an exhibition on Austronesian voyaging histories. In his approach, he gathers recycled materials and constructs depictions of futuristic plastic oceans together with local volunteers. Each iteration is unique, but they all mourn the deteriorated condition of the ocean, the world Māori ancestors once traversed.

In Bottled Ocean 2116, displayed in New Zealand, Nuku describes the ocean as a “vast marae.” The installation is both presenting the state of the ocean and referring to the Māori history of voyaging. With a wharewaka houra (canoe house), Nuku represents the mode through which his ancestors would travel and reconnect with communities. By creating a plastic marae, he intends to portray a place of equality, complementation, and personification. With the process of personifying places, animals, and moments, he intends to pull people closer to things; a practice that, according to Nuku, speaks directly to nature. In later installations, a new addition lies within the cabin: a plastic human skull, ultimately begging the question ‘Will this be our end?’

Bottled Ocean 2120, displayed in Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden, The Netherlands, represents the world in 2120. The ice caps have melted and water has flooded the land. Inspired by the 1995 post-apocalyptic film Waterworld, in which the main character mutates to adapt to his new life and reality under water, Nuku constructed a plastic world of 7,000 plastic bottles together with 230 local volunteers. In contrast with the wharewaka houra in his previous works, this installation offers a new centerpiece: Tangaroa Totem. The Māori sea deity has mutated in accordance with his new reality and is surrounded by plastic sea creatures. But he allows no space for humans.

From Threat to Ancestor

With the various depictions of a wharewaka houra, the Māori sea deity, a human skull, and paintings of microplastics, Nuku paints a clear picture of the threats we face. The world’s current mutation through plastic waste is in such a manner striking that it can be found across oceans, in hammerhead sharks, jellyfish, sea turtles, human blood. Even the sea deity Tangaroa transforms to adapt to his surroundings. The consequence? Human life loses its place in the world, an ocean filled with plastic as our sole legacy. However, his works do not merely highlight the dangers of plastic waste. In all his installations, he picked up materials from the street, materials commonly viewed as harmful, and reframed them. He shows plastic as conduits for water and light, as reflections and revelations.

That is the ultimate message Nuku makes. Through his Māori heritage, he sets out to reshape humanity’s relationship with the environment and plastic. Although often considered a new substance, he argues that a plastic bottle’s genealogy demonstrates it is one of the oldest things around. Made from oil and witnessing the Earth’s ancient processes, the plastic bottle is an ancestor, “and if you think about it that way, like an ancestor, then maybe you can start to think about treating it with respect instead of throwing it in the ocean.” Challenging our perceptions, he turns what is widely considered an environmental threat into a symbol of relationships, ancestry, and transformation. He confronts the impact of plastic pollution on Māori, while revealing the beauty within and connections between plastic and human life. It is plastic that fills the oceans, that finds its way into marine life, and impacts Māori ways of living. And it is plastic that should be honored and revered as our predecessor.

Breaking Into Indifference

With his Bottled Ocean installations, Nuku sends a tough message of confrontation. A plastic bottle disposed of on one side of the world washes up on shore on the other. A process of waste colonialism that not only threatens Māori security, but will spill over into all of humanity. Nuku puts up a mirror to the dismissed impact of people’s choices. However, rather than invoking guilt or hopelessness, he provokes empathy, introspection, and connection. He forces the viewer to cultivate a new relationship with plastic. To see plastic as a beautiful material with a whakapapa. His art then becomes a double-edged sword—not only a mirror to struggle, but also a reflection of strength. With it, Nuku shares a message of intersectional environmentalism through plastic, a practice of storytelling that United Rising deems indispensable to his fundamental intention: to touch the soul, to shift our views, and to urge people to see from each other’s eyes.

That is the biggest challenge for Nuku: the indifference people hold onto. Yet, through his plastic and collaborations with volunteers, he shifts the foundations that move climate conversations. A worldview rooted in deep spiritual connection to the environment diverges from colonial approaches by shifting the way responsibility, repair, and value are thought of—replacing waste, blame, and negligence with divinity, interconnectedness, and beauty.

A prophecy is not set in stone; it is a warning of what lies ahead. It is a call to break into indifference and swim against the tide. As Nuku says: