Author: Letícia Rosar Mori

“The forest is alive. It will only die if the white people persist in destroying it. If they succeed, the rivers will vanish underground, the ground will crumble, the trees will wither, and the rocks will crack from the heat. The parched earth will become empty and silent. The xapiri spirits, who come down from the mountains to play in the forest with their mirrors, will flee far away. Their fathers, the shamans, will no longer be able to call them and make them dance to protect us. (…) When none of them are left alive to hold up the sky, it will fall.” – Davi Kopenawa, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman

Are you familiarized with the term Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)?

Before any major decision is made that could impact Indigenous lands or traditional communities, there’s a fundamental right that must be respected: the right to free, prior, and informed consultation.

The FPIC is both a right and an obligation. This means that Indigenous peoples, quilombola communities, and other traditional populations have the right to be heard and to actively participate in decisions that could affect their territories and ways of life. This isn’t just a formality or a symbolic gesture — it’s a legal right recognized in international law, particularly in the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). At the same time, it establishes a binding duty for the State to engage in meaningful consultation before implementing any administrative or legislative measures that could affect these communities and their lands.

Why are Indigenous territories so important?

We live in a world that, over time, has forgotten where it came from. The Western conception of humanity, often linked to the white, urban civilizational model – the napë, according to the terminology of Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa, has built a deep divide between people and nature, as if nature were something wild, distant, and separate from us.

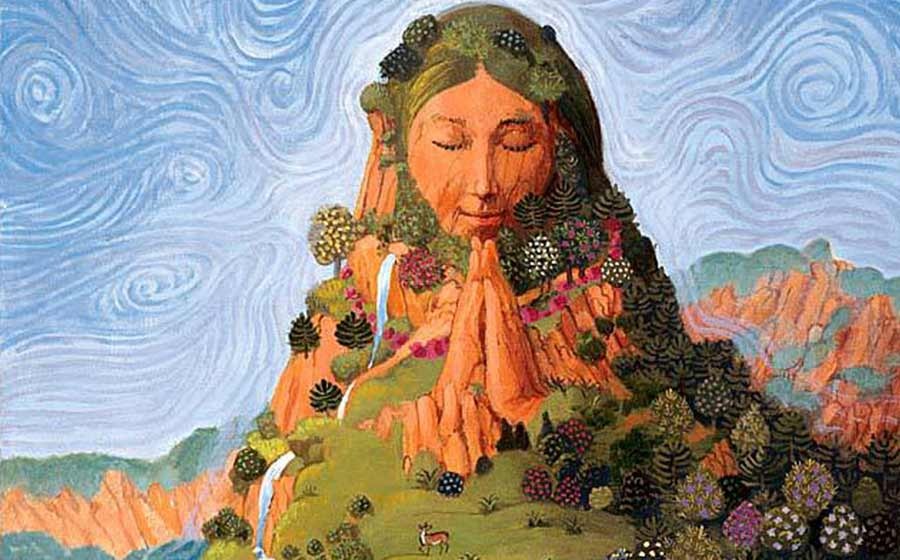

This separation taught us to see nature as a resource, something to be exploited, tamed, sold. But for Indigenous peoples, the Earth has never been a commodity. She is Pachamama, Gaia. A living, sacred being who pulses with ancestral memory and holds the wisdom of a life in balance.

This ancient knowledge, which sees the Earth as a being with its own rights, has already been recognized by constitutions in countries like Bolivia and Ecuador. Yet, Indigenous territories remain under constant threat — not only from chainsaws and dams that scar the land, but also from a quieter, more insidious violence: institutional violence, often disguised as progress or development. These threats hide behind the veil of legality, but their impact is devastating.

For Indigenous peoples, territory is not just land. It is where their gods dwell, where their ancestors rest, where their stories are born. It is where they dance, sing, and heal. It is where they are.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) recognizes the value of “traditional knowledge” — wisdom rooted in the land, passed down through generations in rituals, songs, dances, and celebrations. For Indigenous communities, territory is not merely a physical space. It is a living memory, a spiritual dimension, a vital force that weaves together ancestry, identity, and collective existence.

In his book “Futuro Ancestral”, Ailton Krenak, a renowned Brazilian Indigenous writer, denounces that we are witnessing an emotional collapse in our relationship with nature – a world that now sees the Earth only as an economic asset, forgetting her sacred and vital essence.

This post is an invitation to listen. To listen to those who have never stopped hearing the voice of the Earth. To recognize that protecting Indigenous territories is not only an act of justice – it is an act of collective survival.

Recognizing the Wisdom of the Global South

In a world that insists on imposing a single vision of development, the knowledge of the Global South rises as a voice of resistance and renewal. These ways of knowing not only challenge the Eurocentric logic that places Western civilization at the peak of evolution, but also offer concrete and sustainable alternatives for rethinking how we live, produce, and relate to the Earth.

Rooted in collective experience, spirituality, oral traditions, and deep connections to the land, these forms of knowledge are not relics of the past — they are living tools for transformation. They invite us to see the world differently, to break free from the invisibility imposed by colonialism, and to recognize the legitimacy of diverse ways of existing, resisting, and thriving.

Valuing the knowledge of the Global South is, therefore, an act of epistemic justice, as it challenges the historical marginalization of non-Western epistemologies and affirms the legitimacy of diverse ways of knowing. For instance, Boaventura de Sousa Santos, in Epistemologies of the South, argues that recognizing Indigenous and local knowledge systems is essential to counter epistemicide and promote cognitive justice. In South Africa, community-based research initiatives have demonstrated how engaging with local epistemologies can democratize knowledge production and disrupt academic hierarchies. In Latin America, feminist scholars have highlighted the exclusion of gendered and Indigenous perspectives in climate litigation, advocating for their inclusion as a form of epistemic justice. Similarly, in Brazil, the legal victories of Indigenous communities against projects like Belo Sun and the critique of the Belo Monte dam illustrate how the assertion of traditional knowledge and rights can resist institutional violence and environmental injustice. These examples show that epistemic justice is not only theoretical but also deeply practical, rooted in the lived experiences and resistance of marginalized communities.

It means ensuring that Indigenous peoples, quilombola communities, and traditional populations have their autonomy respected, their ways of life protected, and their ancestral wisdom recognized as essential to building a more just, diverse, and sustainable future.

Inter-American Court Cases Strengthening Indigenous Territorial Rights in Latin America

The jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) has become a powerful force in defending the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples across Latin America.

In the case of Garífuna Community of San Juan and its Members v. Honduras (2023), the Court condemned the Honduran state for failing to uphold the right to collective property and free, prior, and informed consultation. This ruling mirrors the negligence seen in Brazilian megaprojects like Belo Monte and Belo Sun, where Indigenous communities were excluded from meaningful consultation processes.

Similarly, the landmark case of Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni Community v. Nicaragua (2001) recognized the violation of ancestral land rights and reinforced the obligation of states to protect traditional territories.

More recently, in Maya Q’eqchi’ Agua Caliente Indigenous Community v. Guatemala (2023), the Court reaffirmed the right to consultation and protection against unauthorized extractive activities.

These examples clearly demonstrate that Free, Prior and Informed Consent is a powerful mechanism for preventing environmental destruction. By ensuring that Indigenous and traditional communities are meaningfully consulted before any development or extractive project begins, FPIC acts as a safeguard against decisions that could lead to irreversible ecological harm. When communities are empowered to voice their concerns and withhold consent, they can halt projects that threaten their territories, ecosystems, and ways of life. In this way, FPIC becomes a frontline defense against environmental crimes, including ecocide, by placing ethical and legal checks on exploitative practices

FPIC: A Key Mechanism Against Ecocide

In a world where environmental destruction often hides behind the mask of progress, Free, Prior and Informed Consultation emerges as a powerful tool of resistance. More than a right of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities, these protocols are mechanisms for protecting life itself — both human and non-human.

By ensuring that these communities are heard before any project that could impact their territories is approved, FPIC acts as an ethical and legal barrier against the advance of ecocide. It demands that governments and corporations recognize that land is not an empty space to be exploited, but a living entity, home to cultures, histories, and entire ecosystems.

When respected, these protocols can stop the construction of dams that kill rivers, the mining operations that devastate forests, and the deforestation that silences ancestral songs. They are, therefore, instruments of climate justice and biodiversity protection, placing at the center of the conversation those who have always known how to care for the Earth: Indigenous peoples.

Respecting FPIC is not just about following legal procedures. It is about recognizing that there is no future without listening, without dialogue, without territory. Preventing ecocide begins with something as simple , and as powerful, as listening.